Great so I inherited a fear of vietnamese people and agent orange. |

|

Results 1 to 25 of 77

Thread: Let's discuss evolution from a scientific perspective -not for Creationist, anti-scientific argument

-

06-12-2014 01:29 AM #1Diamonds And Rust Achievements:

- Join Date

- Dec 2009

- Gender

- Location

- Center of the universe

- Posts

- 6,949

- Likes

- 5848

- DJ Entries

- 172

Let's discuss evolution from a scientific perspective -not for Creationist, anti-scientific argument

Apparently mice that are taught aversion to a particular smell will pass on that aversion to their offspring, even if the offspring have never encountered the smell themselves and have no reason whatsoever to associate it with fear or aversion, according to this NatGeo article:

Mice Inherit the Fears of their Fathers

Do these experiments point to the possibility that natural selection isn't as random as it's believed to be, at least among the Dawkins-style "Selfish Gene" camp? If newly-acquired knowledge can be encoded directly into DNA and passed on to the next generation, what does that mean about the supposed randomness of genetic mutations?

I'd appreciate hearing from anybody who knows more about the subject of evolutionary biology and especially this interesting subject of possibly directed mutation.

***Please note change in the title. Added this: not for Creationist or other anti-scientific arguments

Please respect thread starters parameter for this debate. - adminLast edited by gab; 06-17-2014 at 05:16 AM.

-

06-12-2014 01:47 AM #2D.V. Editor-in-Chief

- Join Date

- Jun 2006

- LD Count

- Lucid Now

- Gender

- Location

- 3D

- Posts

- 8,263

- Likes

- 4140

- DJ Entries

- 11

Everything works out in the end, sometimes even badly.

-

06-12-2014 01:49 AM #3Diamonds And Rust Achievements:

- Join Date

- Dec 2009

- Gender

- Location

- Center of the universe

- Posts

- 6,949

- Likes

- 5848

- DJ Entries

- 172

Trolled in the 1st post loool!!!

-

06-12-2014 02:30 AM #4Natural selection isn't random, the mutations are. But as this article seems to be about epigenetic inheritance, it has nothing to do with mutations of the actual nucleotide sequences. It's a change in either the expression of the gene or the function of the gene instead of the genotype itself.

Originally Posted by Darkmatters

Originally Posted by Darkmatters

Epigenetics - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Epigenetic Inheritance - Modern Genetic Analysis - NCBI BookshelfThe worst thing that can happen to a good cause is, not to be skillfully attacked, but to be ineptly defended. - Frédéric Bastiat

I try to deny myself any illusions or delusions, and I think that this perhaps entitles me to try and deny the same to others, at least as long as they refuse to keep their fantasies to themselves. - Christopher Hitchens

Formerly known as BLUELINE976

-

06-12-2014 02:55 AM #5Diamonds And Rust Achievements:

- Join Date

- Dec 2009

- Gender

- Location

- Center of the universe

- Posts

- 6,949

- Likes

- 5848

- DJ Entries

- 172

Awesome, thanks for responding Blueline. That first article gets way too dense with scientific jargon for me, but I did glean from it and from what you said that epigenetic inheritance isn't a change in DNA that could create a new permanent mutation, so it doesn't affect evolution. Apparently just a few generations inherit the trait, and then I suppose it fades out?

Still it's intriguing that such a trait can be passed on directly at all, rather than through parents teaching the children. I wonder about the possibility of this (epigenetic inheritance) or something similar contributing to actual genetic mutation.

-

06-12-2014 03:12 AM #6

I suppose it's possible that some parts of the DNA is malleable in such a way, that classical conditioning can be transferred onto offspring. It makes a lot of sense, because it would allow very quick adaptation between generations, like say if a certain sound or smell indicated a danger/food/whatever, then the offspring would also instinctively be aware of this.

---------

Lost count of how many lucid dreams I've had

---------

-

06-12-2014 03:19 AM #7

I'm not particularly well-versed in epigenetics (it hasn't been a major focus of any of my classes, and I'm about a year away from getting my BSc in biology), but I don't know if it couldn't play a role in evolution by natural selection. Whether a gene is expressed or not, or whether its function is altered, might have some role in how an organism is adapted to its environment. To what extent, I have no idea. But the main point is that epigenetic inheritance does not relate to the nucleotide sequence (the actual base-pairs of the DNA strand - the adenine, cytosine, guanine, and thymine molecules).

I have no idea. Did the original article say this? I didn't read it thoroughly.Apparently just a few generations inherit the trait, and then I suppose it fades out?

It is weird, and much cooler than regular old genetics IMO. It reminds me of Lamarckian evolution (where, for example, a giraffe has a long neck because its ancestors would literally stretch their own necks to reach food high in a tree. Evolution doesn't work like that, but with epigenetic inheritance, Lamarckism may not be as wrong as previously thought?). In fact: Lamarckism - Wikipedia, the free encyclopediaStill it's intriguing that such a trait can be passed on directly at all, rather than through parents teaching the children. I wonder about the possibility of this (epigenetic inheritance) or something similar contributing to actual genetic mutation.Last edited by BLUELINE976; 06-12-2014 at 03:23 AM.

The worst thing that can happen to a good cause is, not to be skillfully attacked, but to be ineptly defended. - Frédéric Bastiat

I try to deny myself any illusions or delusions, and I think that this perhaps entitles me to try and deny the same to others, at least as long as they refuse to keep their fantasies to themselves. - Christopher Hitchens

Formerly known as BLUELINE976

-

06-12-2014 03:34 AM #8Diamonds And Rust Achievements:

- Join Date

- Dec 2009

- Gender

- Location

- Center of the universe

- Posts

- 6,949

- Likes

- 5848

- DJ Entries

- 172

The article did say that 2 generations of mice inherited the smell aversion, but that's all it said on that count. I assumed the trait wouldn't be permanent because, if it was, then wouldn't that constitute a mutation and cause an evolutionary change? I'm still pretty confused about the difference.

-

06-12-2014 04:33 AM #9

Well, a genetic mutation would be changing the actual DNA sequence. An epigenetic modification doesn't affect the DNA sequence. Rather, it affects whether a gene is expressed/turned on, or how much it is expressed, or how the gene functions. This site should be helpful: Epigenetics

If I understand it correctly, epigenetic inheritance works by the addition or removal of certain epigenetic tags that are attached to the DNA and/or histones in response to outside signaling. Histones are proteins that the DNA is wrapped around. They serve two basic purposes: gene expression regulation and space-saving. They help compact the DNA strands so that everything can fit in the nucleus of a cell. But in doing so, they also affect the availability of the genes on the strand to be copied. If they're too compact, they can't be transcribed. This is where the epigenetic tags come in. Each cell type will have a certain epigenetic tag blueprint. One of these tags is a simple methyl group (-CH3), and it seems that DNA that is heavily methylated tends to be transcriptionally inactive. So you can probably understand that changing an epigenetic tag layout may change what kinds of genes are expressed, and in turn change what kinds of proteins a cell will pump out, and what those proteins will go on to do in the body.

You can think of the tags as switches, and the histones as dials. The tags determine whether the gene will be expressed, and the histones determine how much (by changing the physical availability of a gene on the DNA strand).

I think this section of the wiki can answer your question fairly succintly: "These epigenetic changes may last through cell divisions for the duration of the cell's life, and may also last for multiple generations even though they do not involve changes in the underlying DNA sequence of the organism; instead, non-genetic factors cause the organism's genes to behave (or "express themselves") differently."The worst thing that can happen to a good cause is, not to be skillfully attacked, but to be ineptly defended. - Frédéric Bastiat

I try to deny myself any illusions or delusions, and I think that this perhaps entitles me to try and deny the same to others, at least as long as they refuse to keep their fantasies to themselves. - Christopher Hitchens

Formerly known as BLUELINE976

-

06-12-2014 07:33 AM #10Diamonds And Rust Achievements:

- Join Date

- Dec 2009

- Gender

- Location

- Center of the universe

- Posts

- 6,949

- Likes

- 5848

- DJ Entries

- 172

Ok, that clears things up a lot - especially the last part, thanks for that.

Here's the thing that always kind of bugged me about evolution via natural selection (as a complete layman who's only exposure was to read Dawkins' Mount Improbable and a bunch of Sagan books) -

It just seems to strain credibility that almost any species at all manage to generate viable mutations when environmental conditions threaten their existence.

I mean - how does that work?

Are there constantly mutations happening and the vast majority of them never lead to new species because the environment doesn't necessitate it (not that I'm expecting you to know this Blueline… just conjecturing)? Punctuated equilibrium is a thing, isn't it? Meaning that evolutionary changes generally don't happen for long periods of time, until environmental changes make it necessary to change or die out, and suddenly wham! New species pop up.

It just seems to me (again, as a layman) that it would make sense if somehow the genes are actually responding to environmental pressure. I'm not saying that's definitely what happens - of course nobody knows. But it seems like if evolution really happened only through random mutations that happened to coincide with environmental changes that select in favor of those exact changes - it sort of seems like new species would almost never happen. Or am I sounding like a Creationist? I absolutely don't mean to imply any Creator who's pulling the strings, just to make that clear! Just some hitherto unknown mechanism that causes genes to respond to changing conditions and generate new mutations of specific types. Not because that's what an animal or species WANTS to happen consciously of course - like some species of dinosaur thinking "Wow, wouldn't it be cool if we could grow wings and fly around, and maybe our scales could change into feathers… ". Or "Let's change into banandas". I don't mean to propose any particular mechanism, just saying…Last edited by Darkmatters; 06-12-2014 at 07:36 AM.

-

06-13-2014 12:42 AM #11

Your post is a little confusing, so I'm not exactly sure what you're asking. But here is quick overview of mutations and natural selection, and a link to a page that describes punctuated equilibrium.

Most mutations are neutral; they neither help nor hurt the organism. Imagine you have a codon in a DNA template that codes for the amino acid alanine, which will then go on to be part of a protein/enzyme. There are four sets of codons that can code for alanine: GCU, GCC, GCA, and GCG. If you have a DNA template that reads CGA, then if the RNA polymerase (which transcribes DNA into mRNA) is working correctly, you will get GCU, which codes for alanine. But if the RNA pol. makes a mistake, it can transcribe CGA incorrectly, perhaps as GCA. But that won't have any effect on the final protein, since GCA also codes for alanine.

Mutations happen all the time, and as I just explained, most are neutral. But whether a mutation is beneficial or deleterious depends on the organism's environment. A mutation that is beneficial for one organism may be harmful to another. Whether a mutation (or group of mutations) is selected for in an environment is where the randomness stops. The mutations are random (i.e we cannot predict them, AFAIK), but their continued existence is not (if they are beneficial).

Punctuated equilibrium: Evolution 101: The Big IssuesLast edited by BLUELINE976; 06-13-2014 at 12:45 AM.

The worst thing that can happen to a good cause is, not to be skillfully attacked, but to be ineptly defended. - Frédéric Bastiat

I try to deny myself any illusions or delusions, and I think that this perhaps entitles me to try and deny the same to others, at least as long as they refuse to keep their fantasies to themselves. - Christopher Hitchens

Formerly known as BLUELINE976

-

06-13-2014 02:15 AM #12Diamonds And Rust Achievements:

- Join Date

- Dec 2009

- Gender

- Location

- Center of the universe

- Posts

- 6,949

- Likes

- 5848

- DJ Entries

- 172

I was just basically restating the thread's premise, not asking a question with any straightforward answer. To word it a little differently in hopes some people might join in - I wonder if it's possible that mutations can respond to environmental pressure, rather than just being completely random?

I know that according to the Dawkins-style theory mutations are completely random, but is it a known fact that this is so?

-

06-13-2014 04:46 AM #13

A mutation is just a change in the DNA code, so it doesn't make sense to ask if a mutation can respond to environmental pressure. DNA can be changed by the environment; think of what prolonged and repeated sun exposure can do to skin cells (melanoma). But I don't think DNA can change itself in the context of responding to environmental pressure. That's where epigenetics becomes more relevant, I think.

The worst thing that can happen to a good cause is, not to be skillfully attacked, but to be ineptly defended. - Frédéric Bastiat

I try to deny myself any illusions or delusions, and I think that this perhaps entitles me to try and deny the same to others, at least as long as they refuse to keep their fantasies to themselves. - Christopher Hitchens

Formerly known as BLUELINE976

-

06-14-2014 07:07 PM #14Banned

- Join Date

- Aug 2005

- Posts

- 9,984

- Likes

- 3084

This isn't the case. There are a couple of things to clarify.

The first is what Blueline said: evolution doesn't work by organisms generating mutations in times of environmental stress. Rather, they're generating them all of the time. Most of these mutated genes are fairly harmless, and lots of them actually have no effect at all on their carriers because the gene is recessive. So the mutated genes are latent in the population all the time. It's only when the environment changes that selection will occur - but this isn't when the mutation is occurring. For example, chickens still have the genes for teeth, but these genes are ancient. If their environment were to change so that toothed chickens had an advantage, then natural selection would occur and toothed chickens would branch off from the population. But that's not when the mutation occurred, it occurred long ago.

Secondly, evolution doesn't work by "almost all" species adapting their way out of an environmental crisis. Most species who suddenly can't survive in their environment will simply die out. Evolution isn't usually about quickly adapting to survive in new conditions; it's about gradually adapting to benefit from new opportunities (called "niches"). For example: the strain of bacteria which can now metabolise nylon, which did not exist until a few decades ago. The original bacteria species wasn't under threat, but some of those bacteria, after some time, had a mutation which created an enzyme which could metabolise nylon. No other organisms were doing this, so there was a new source of free energy for these bacteria to live off. In this way the mutation spread and a new species was born. This is called "radiative adaptation" because life is radiating outwards into an empty gap. This occurred en masse after the event which killed the dinosaurs. The dinosaurs did not quickly adapt and survive; they all died out. The important thing though was that this left a huge number of niches free. The mammals in particular capitalised on this opportunity, gradually evolving over thousands of years to occupy the niches, which gave us most of the large variation of mammals we see today.

Mutations are just chemical events. A random mutagen comes along and collides with a random bit of DNA, changing the base sequence in a random way. Clearly there's nothing "guided" about this process. That's impossible, it would require the DNA to somehow "know" what it coded for, know what the environmental changes were, and come up with a plan to modify itself - and we can see that's just not how the process happens.

These mice experiments are fascinating and ground breaking, although it's early days in terms of whether the results will be vindicated. But what's happening, if it is happening, is not a directed mutation of the DNA. The mutated feature is already there; it's the gene which controls sensitivity to the aroma. This evolved long ago, via blind natural selection. What's happening is a modification the level of expression of this gene, which is called epigenetics. This is not done by the DNA; it's done by various enzymes acting on the DNA. In other words, it's more akin to a feature of the organism - just like the enzymes which control sensitivity to the aroma, or any other kind of gene - than it is to a feature of the DNA. Therefore there's nothing strange about in acting in a "directed", non-random way; it's a feature of the organism, acting in the organism's interests, and like any other feature, it evolved by blind natural selection.

-

06-14-2014 10:45 PM #15Diamonds And Rust Achievements:

- Join Date

- Dec 2009

- Gender

- Location

- Center of the universe

- Posts

- 6,949

- Likes

- 5848

- DJ Entries

- 172

Excellent - thanks for typing all that up Xei. It explains a lot.

-

06-15-2014 06:27 AM #16

I have to read this thread yet - thanks for making it Darkmatters!

But if it's not mentioned already - I read something about this study lately - maybe on neuroskeptic.

The tenor was - yes they found something special - more study will commence.

But no - it does definitively not mean, that a specific fear is directly inheritable.

The hype in the media not being justified because of a, b, c ...Last edited by StephL; 06-15-2014 at 06:38 AM.

-

06-15-2014 07:20 PM #17

Text from your link, Darkmatters, a bit edited by me to bring out the points which I find esp. interesting:

Fascinating stuff - so they consider free receptors in the bloodstream reaching the gonads and being taken on board by sperm as a mechanism besides classical epigenetics, too!Dias trained mice to fear acetophenone over three days, then waited 10 days and allowed the animals to mate. The offspring show an increased startle to acetophenone (with no shock) even though they have never encountered the smell before. And their reaction is specific: They do not startle to a different odor.

The scientists also looked at the F1 and F2 animals’ brains. When the grandparent generation is trained to fear acetophenone, the F1 and F2 generations have more “M71 neurons” in their noses, Dias said. These cells contain a receptor that detects acetophenone. Their brains also have larger “M71 glomeruli,” a region of the olfactory bulb that responds to this smell.

”What is striking is that the neuroanatomical results still persist after IVF (in vitro fertilization),” Dias said. “There’s something in the sperm.”

“Do you have any idea of how this information being stored in the brain is being transmitted to the gonads?” a questioner asked.

The short answer is that the researchers don’t have any idea, though they’ve thought about several possible explanations.

Apparently a study in cats and pigeons showed that after smelling an odor, the odorant receptor molecules can get into the blood stream, and other studies have reported odorant receptors on sperm. So maybe the odor molecules get into the bloodstream and make their way to sperm.

Another possibility is that microRNAs — tiny RNA molecules involved in gene expression — get into the bloodstream and deliver odor information to sperm.

The first one is a good and probably not yet answerable question.

As to the second one - it is not fear, what the offspring inherit - they inherit having more olfactory receptors in the nose and a bigger brain-region, which belongs to these receptors and their detective work on acetophenone. And they react with startle when exposed to it.

How the neuroanatomic features in the offspring correlate with this reaction - behaviour - is not clear, as far as I understand it.

I also believe, there is some way, in which epigenetic happenings will enter into the hard code. We lack understanding of these processes, though, as far as I know.

Yes. The environment, inner workings of the mind and actual behaviour change at least neuroanatomy without a doubt. Since these mice startle, and are not just only more sensitive to registering the stuff olfactorily - there must be more than just a lowered detection threshold, I guess.

Or are there so many receptors then, that smelling some of the stuff leads to startle because of unusually intense olfactory sensations in general?

Since olfactory information is so crucial to detect danger and avoid it, maybe it's just enough to have a really unusual intensity of any smell to generate startle? Startle is not avoidance after all - only a raise in directed attention. But then - the olfactory bulbs, they talk about here, are in contrast to other sensory processing brain-areas literally and directly a part of the famous, emotion generating limbic system. So maybe an emotional content, or at least a negative association, could lie directly in the bulbs, where they did find modifications, see above. Fascinating! Very!!

I have some sweet material at hand, from collectively taking this thread: http://www.dreamviews.com/religion-s...ns-here-6.html on the path of evolution for the time being.

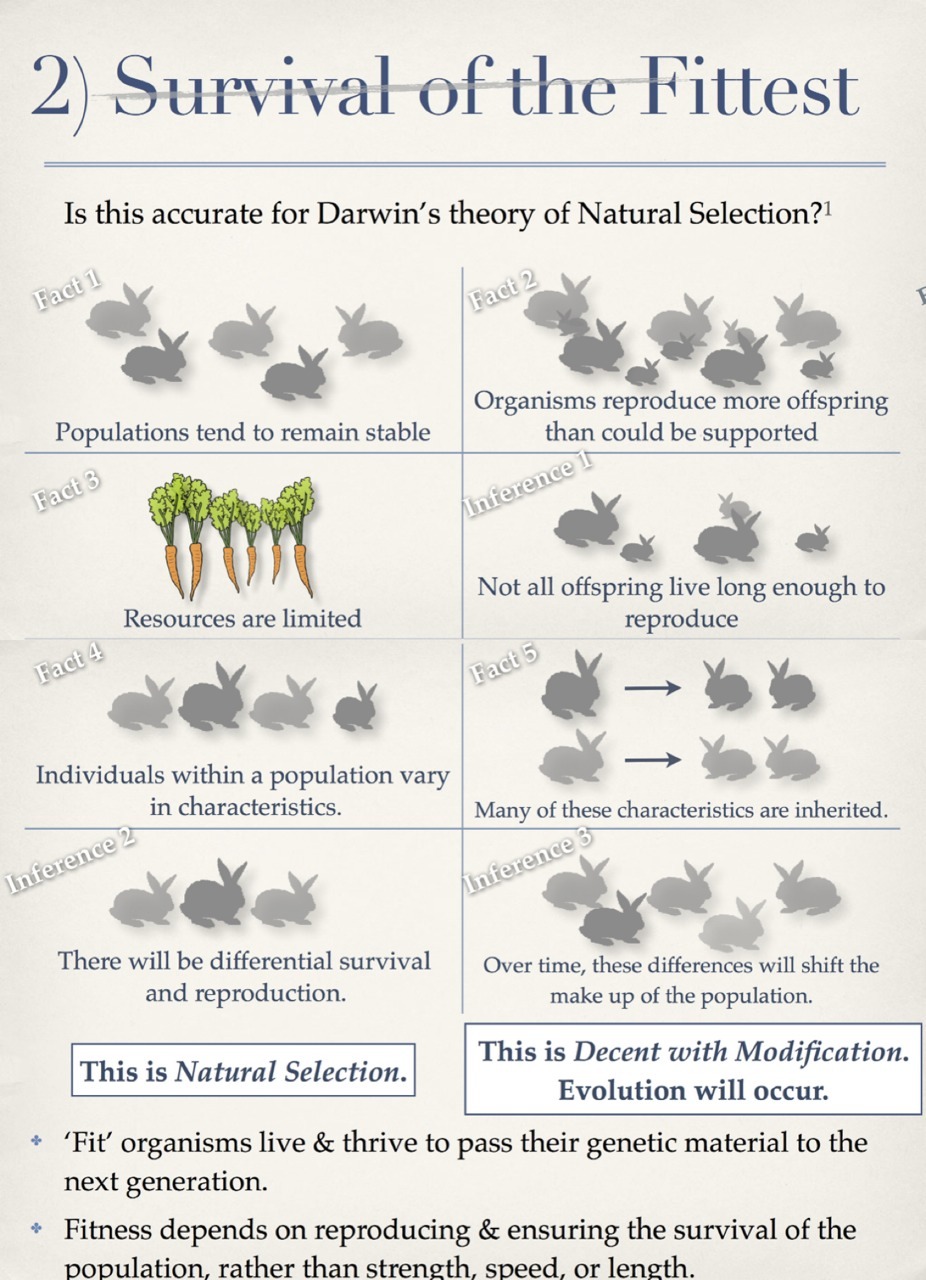

It could be helpful - your missing link might be "decent with modification":

And seriously - the following video, courtesy UM, is not only super-sweet and hilarious - it is great concerning the information being presented - clear and concise, a broad and quite comprehensive overview on the basics.

I think, you might find suitable explanations for some of your questions:

Last edited by StephL; 06-15-2014 at 11:35 PM.

-

06-16-2014 01:24 AM #18Diamonds And Rust Achievements:

- Join Date

- Dec 2009

- Gender

- Location

- Center of the universe

- Posts

- 6,949

- Likes

- 5848

- DJ Entries

- 172

Thanks Steph, all of that is very helpful!

See, now this stuff is fascinating to think about!

This idea is very intriguing. So if I understand correctly, there are a lot of these old recessive mutations stored in the DNA, and if one of them becomes useful in a changing environment it can or will 'take effect'? I don't know the terminology. I'm curious about how long it would take for instance for toothed chickens to develop if it becamenecessaryuseful. Several generations? One? Dozens? Does this mean for instance that modern humans might have recessive genes for thick body hair, or for feet that look like hands, with opposable 'thumbs' (yeah, like in AeonFlux, or the Beast)? And that in the right environmental circumstances these traits could become 'reactivated'?

And when this happens - when these recessive traits become reactivated, that's not called evolving? I'm getting the sense that it isn't evolution unless it changes the DNA, and/or maybe creates a distinct new species?Last edited by Darkmatters; 06-16-2014 at 01:29 AM.

-

06-16-2014 02:17 PM #19

I can't answer this specifically out of thin air - but I might get back to you on it.

I needed to do some reading up first - my university studies were a long time ago.

But what is maybe also interesting to know here, is that while we develop after conception and into a complete birth-rife baby - we undergo what is called ontogeny or morphogenesis. And the funny thing is, that we develop our final shape by taking the "evolutionary route" - which is called phylogenetics.

So that means, that an embryo starts out with gills for example - and that is not for breathing in the uterus. Otherwise we needed them until birth. An embryo gets oxygen directly from the mother's blood, only after birth do the lungs unfold and breathing starts.

But first come gills, which then develop away into other structures.

So some of these silent genes are not even always silent - they come to expression in the womb, and then get deactivated again.

I can tell you, how evolution is currently defined: Changes in allelic frequency.

If we map the different forms of genes (alleles) of a population and after a few generations, the frequency changes - evolution has occured.

Allele frequency - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

That still doesn't answer your question completely, though.

But I can tell you something, which you might find fascinating.

In case of malignant tumours - it can happen that all sorts of genes get "mis-activated" and in places, where they do not belong at times.

Gene expression is regulated not only to switch on "human" so to speak - but you need to activate exactly the correct genes for a certain sort of adult cell in the organs. Every cell has all of the organism's genetic information - but you do not want teeth in the brain for example, or hair.

But exactly this can happen, and among freaky illnesses - this tumour is a star: the 'Craniopharyngeoma'. It develops from "omnipotent" embryonic stem cells in the pituitary gland. Mainly in children - and yupp - a brain-tumour with teeth and hair and other features in it results:

The stuff in the middle is not supposed to be there.

One thing though - your offspring cannot inherit your body-cell tumour - neither this one from embryonic stem cells.

Only what is in the gametes (eggs and sperm) can be passed down - not what is somewhere else.

Now men produce fresh sperm all the time - while females make their eggs once and for all while they are still in the womb. The eggs get released one at a time (well or two = non-identical twins etc.) during her fertility phase, however I should call it in English..?

That is also why it is genetically dangerous to get a child late in life as a woman, while age does not - or by far not so much - matter in men.

While time goes by - more and more mutations, brought about by chance or environment, will heap up in these eggs with their half set of chromosomes. Meaning mistakes and even disastrous mistakes are more likely to occur - mainly spontaneous early abort.

A famous other example is Down-syndrome = Trisomy 21. What happens here, is that children end up with one chromosome 21 too many -

a chromosomal aberration as opposed to a point-mutation, which happens on the level of genes with their base-pairs.

To make sure, I do not come over as doing something like vaccination-scaremongering here with maternal age, despite me really knowing this -

I'll spoiler you the respective part from Wikipedia:

Menopause comes very late in some women - even in their 60s, or in freak cases even later. I believe to remember a 70 year old giving birth in India a while ago, but with taking oral hormones - resulting in 6-fold "twins", all healthy, but it's madness and irresponsible in my eyes.Spoiler for Trisomy 21 prevalence/risks with maternal age:

Buut - evolution can occur like this as well - a point-mutation, or a whole bunch of them in the gametes, can of course result in an unusual genotype (the overall genetic make-up), and as a result an unusual phenotype (the actual shape of an organism) in the offspring. And that organism might be something special in a positive way!Last edited by StephL; 06-16-2014 at 04:12 PM. Reason: more eggs and sperm and stuff ..

-

06-16-2014 05:00 PM #20Banned

- Join Date

- Aug 2005

- Posts

- 9,984

- Likes

- 3084

I think the key thing to point out in order to answer your question is that there are always a small number of mutants in the population. It's not a matter of the mutation only becoming "active" when the environment changes. There are probably a few chickens with teeth living right now, and there always are. It's just that currently, that's not advantageous, so those particular chickens don't produce as many children and the mutation doesn't spread... it just keeps appearing sporadically at the same rate. But if the environment were to change, then they would have more progeny relative to their peers, and so the mutation would quickly spread throughout the whole population. Another random example is people with "werewolf syndrome" whose faces are covered in fur. Let's say for the sake of illustration that this is caused by a recessive mutated gene. So, there always a small number of people with one copy of the gene, but it doesn't affect them, so they reproduce at the normal rate and the gene stays in the population. But in the rare case that two people with the gene procreate and produce a child with two copies of the gene, that child will have the condition. So a very small number of these people always exists in the population. Normally they don't have as many children and so the werewolf feature dies away. But say we suddenly found ourselves in another ice age. Those people might be compensated by the extra warmth to such a degree that they survived more than other people and thus had more offspring; and therefore werewolf syndrome will clearly spread through the population.

This is just a semantic issue, really. Evolution is more of a topic than a strictly defined scientific event. It's defined as "inherited change in generations of organisms over time", which is quite general and vague. A mutation spreading throughout the population due to, for example, a change in the environment, is evolution "en masse" because it's a general change to a whole population of organisms. A single chicken being born with an unusual (but unoriginal) trait... you could say is evolution on the scale of single organisms. The fact that it's not a new mutation doesn't rule it out as evolution... there was no new mutation in the "en masse" example either, it was just an old mutation changing its prevalence, but that's definitely evolution. Evolution doesn't even have to be "directed"; sometimes a variation of a gene dies out just by random, not because it was inferior (a process called "genetic drift").And when this happens - when these recessive traits become reactivated, that's not called evolving? I'm getting the sense that it isn't evolution unless it changes the DNA, and/or maybe creates a distinct new species?

-

06-16-2014 05:08 PM #21

This is what I termed 'descent with modification'.

It can be said a bit more specifically, as I did above - the key term is: 'changes in allelic frequency'.

"If we map the different forms of genes (alleles) of a population and after a few generations, the frequency changes - evolution has occurred.

This definition is is the best description to date that captures the ever-changing living world."

I quote from the rest of the info-graphic which is not here.Last edited by StephL; 06-16-2014 at 05:27 PM. Reason: fiddling - but not wanting to make a long post again ..

-

06-16-2014 06:06 PM #22Banned

- Join Date

- Aug 2005

- Posts

- 9,984

- Likes

- 3084

Yeah, that's a good definition for these purposes.

What I meant when I said that "evolution" was more of a broad conceptual structure than a single process is, for example, that "evolution" also refers to the fact that any two species has a common ancestor, and that thus we're all on the same tree of life - which is a distinct concept from changes in allele frequency.

Going back to the original question for a moment, elaborating on what I said about epigenetics being more akin to a feature of the organism than a feature of its DNA: it may also help to think in the following terms. We're already okay with the idea that a mouse may have a mutation which makes it averse to, for instance, cyanide. This is a helpful feature for whichever mouse has it, so by natural selection it becomes prevalent. The feature in the article is not so very different. The difference is that it's more like a "meta feature"; it's a feature which benefits the next several generations, rather than the first mouse to receive it. It doesn't do anything for the first mouse... but if that mouse learns to be averse to a certain chemical, its progeny will be also. So this "meta-feature" of the next few generations of mice (rather than a feature of one mouse) is positively selected for over time. The reason we find it weird is that the specific physical mechanism which this feature uses to transmit the information is closely linked to the genetic material itself. Of course, the genetic material is also what codes for the meta-feature in the first place, so we have something of a confusion of levels. It's easier to understand if you pretend that the meta-feature used some different physical mechanism... for instance, if the mutation instead caused the first mouse to constantly sing "don't eat chemical X" for the rest of its life, including to its children. Or perhaps if it caused the first mouse to feed its babies special food which somehow increased the expression of the "don't eat chemical X" genes in its babies. This we're okay with; it's just a weird case of natural selection. What's really happening is analogous, but the message isn't being transmitted via song or via special food: it's being transmitted via chemical processes acting on the chromosomes.

-

06-16-2014 06:14 PM #23Member Achievements:

- Join Date

- Mar 2008

- LD Count

- In DV +216

- Gender

- Location

- In a Universe

- Posts

- 992

- Likes

- 1135

- DJ Entries

- 88

Hi there!

I don't know if it comes to the discussion here and if you already know it, but some time ago I was discussing with my brother about evolutionism and he showed me the following documentary that let me thinking about the complexity of mutations and natural selection:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VekUf325SHM

I think it's something to take into account too, when talking about the subject of evolution.

-

06-16-2014 06:25 PM #24Banned

- Join Date

- Aug 2005

- Posts

- 9,984

- Likes

- 3084

There's no such thing as "evolutionism" any more than there is such a thing as "gravityism". Evolution is an observed fact with mountains of evidence, some nice descriptions of which you can find here:

Evidence of common descent - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

With respects to "irreducible complexity", no instance of irreducible complexity has ever been found in nature. A classic example of claimed "irreducible complexity" was the flagellum of a bacteria, which requires many separate parts to function. But this was disproven: in fact, there are bacteria in nature which only have around half of the parts required for a flagellum, but they use it for a completely different purpose; for injecting toxins. You can read about that here:

Irreducible complexity - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Another common claimed example is the eye, but you only need to actually look at the animal kingdom to discover many sequential steps in complexity. You can read about that here:

Evolution of the eye - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

And there's a cool video here:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7jEhzAn1hDc

I recommend you also show all of this information to your brother.

-

06-16-2014 07:23 PM #25Member Achievements:

- Join Date

- Mar 2008

- LD Count

- In DV +216

- Gender

- Location

- In a Universe

- Posts

- 992

- Likes

- 1135

- DJ Entries

- 88

^^Actually I showed him other videos including one I saw in one of the @StephL's threads to answer my brother's comment. I liked the eye one you posted there because it was something I was looking for to understand the disposal of the photo sensors inside of it although that's not the subject of this thread.

What is still unclear to me is the random origin of the DNA instructions sequence, which I can only argument that possibly life didn't start on earth.Last edited by Box77; 06-17-2014 at 02:33 PM.

Similar Threads

-

Understanding Energy Healing From A Scientific Perspective

By nina in forum Inner SanctumReplies: 2Last Post: 10-25-2010, 04:12 AM -

What You Ought To Know - The Scientific Method

By Xedan in forum Science & MathematicsReplies: 75Last Post: 05-24-2010, 02:46 AM -

Scientific explanations?

By gsoldi in forum General Dream DiscussionReplies: 3Last Post: 11-08-2008, 10:54 PM

123Likes

123Likes LinkBack URL

LinkBack URL About LinkBacks

About LinkBacks

Reply With Quote

Reply With Quote

Bookmarks